When Zinatara “Zina” Manji, a BSPh, PharmD, and MS graduate of the college, was three years old, she and her extended family were expelled from their native African country in an act of ethnic cleansing.

Manji, currently of New Jersey, is now thriving in her role as the senior director of regulatory affairs where she is the regulatory lead for innovation at GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Consumer Healthcare. GSK is one of the largest research-based pharmaceutical companies in the world. Manji excels in a key role that taps into her unique strengths. Her work helps people take the reins of their own health.

Manji’s parents, personal and professional contacts, and own inner resources were steady guides on her journey to success and meaning.

Her story includes an international airlift operation, salt-of-the-earth Iowan communities, a sewing machine, a motel, and a great female mentor. And of course, the UI College of Pharmacy.

Suddenly Stateless

Like her parents before her, Manji was born in the eastern African country of Uganda.

Manji’s father worked for an American company, among others. Her mother worked at a bank and loved to sew; her sewing machine was always humming. Like many other immigrants of Indian descent, they were Muslim. The schools were good—both her parents completed their education in the British school system—and the country was safe.

Everything changed on August 4, 1972. Without warning, Ugandan President Idi Amin ordered the expulsion of the country’s Asian minority. It was by all accounts an act of ethnic cleansing. Amin gave a November 8 deadline for the roughly 80,000 people of South Asian descent to leave, or be sent to internment camps.

As a result, the family left Uganda on for an Italian refugee camp in Naples. The United Nations had put out a call to countries around the world to help, and the refugees submitted applications to be chosen for resettlement. Most went to England and other countries. After three days in the camp, Manji’s family was selected as part of the 1,000 people to be resettled in the U.S.

“It made sense,” Manji said. “My dad had worked for an American company in Uganda, and my parents had gone through the British educational system. My parents were a young English-speaking couple.”

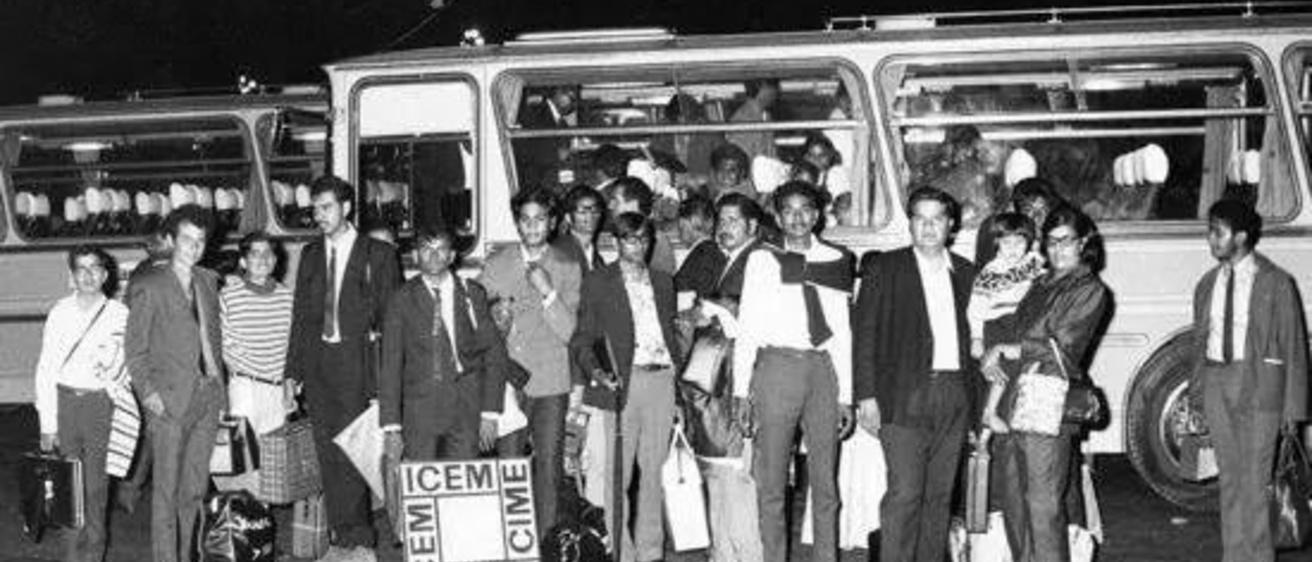

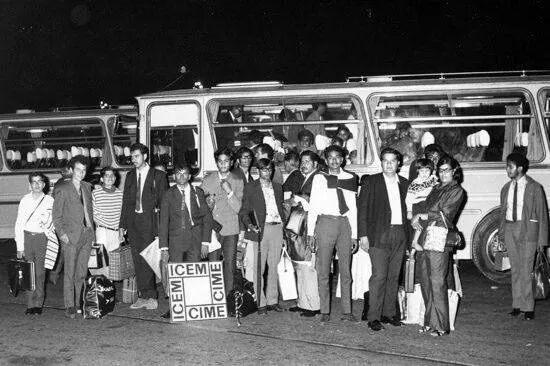

A photo was taken of Manji and her parents standing outside of a bus on one leg of the journey. Her mother is holding her and a group of people are posing outside the bus.

“Just look at them,” Manji said. “They are weary travelers who had months to leave their homes and lives, and look and what they are wearing. They are all dressed up in what looks like business suits. Talk about resilience.”

A Fresh Start

In all, 1,000 Asians immigrated to the U.S., after private organizations banded together to promise to help them find jobs and homes, according to a New York Times article. Christian organizations also participated, led by the Church World Service. Manji and her parents were taken in by the Marion Christian Church.

Once resettled, the family lived in Marion, and then Cedar Rapids, before moving to Mount Vernon to run a motel there just before Manji started high school. Manji attended Bible school at the sponsoring church, which she said felt welcoming despite the differences in religious beliefs, which she commented, “were really not so different.” At first, her mother would act as her translator to new friends and neighbors.

“We became part of the community,” Manji said. “The church helped us find an apartment. Then we bought a house. They helped my dad find a job.”

Unique Pharmacy Path

Manji was originally a pre-med major at Iowa but decided she would be able to specialize more quickly by switching to the College of Pharmacy. From there, her mentor, the late Mary Berg—the first woman promoted to professor in the college—took her under her wing and helped guide her career.

She worked her way through school at the Iowa Drug Information Service (IDIS), and found it “fascinating” to read through the document the FDA produces after a drug is approved. She would hunt through these files for drug information. “It gave all the details of what they consider when reviewing a drug. I really loved how things were negotiated and presented to the FDA as part of the drug approval cycle.”

Manji saw those approval documents again during work experiences as a graduate student at what is now GSK. She was hired after graduation and has stayed with the company for 22 years, including leading regulatory affairs teams and supporting products on the market as well as new innovations.

She gets excited about ideating potential new innovative products that help patients take control of their health, such as digital health technology and drug products. She enjoys successfully ushering innovations through the regulatory process and to market.

“What’s so fascinating with some new technologies is what we can learn from new ways of understanding the healthcare journey of individuals,” Manji said.

“For example, diabetic patients routinely check their blood sugar, adjust it with insulin injections or sugar intake, and have checkups.”

“More and more, there’s going to be a focus on that self-care aspect that is happening away from the clinic and at home. We can look at how people are experiencing and treating disease on a daily basis and how well it’s working. Making the patient a better patient is self-care,” Manji said.

“We’re in an amazing time where innovators and visionaries are re-defining healthcare. I’m inspired to create regulatory strategies for innovations that help people live well.”